Political and economic outlook for Latin America in 2023

Latin America’s trilemma: tough trade-offs on the economy and politics will shape the business environment in 2023, writes Theodore Kahn, Associate Director, Control Risks...

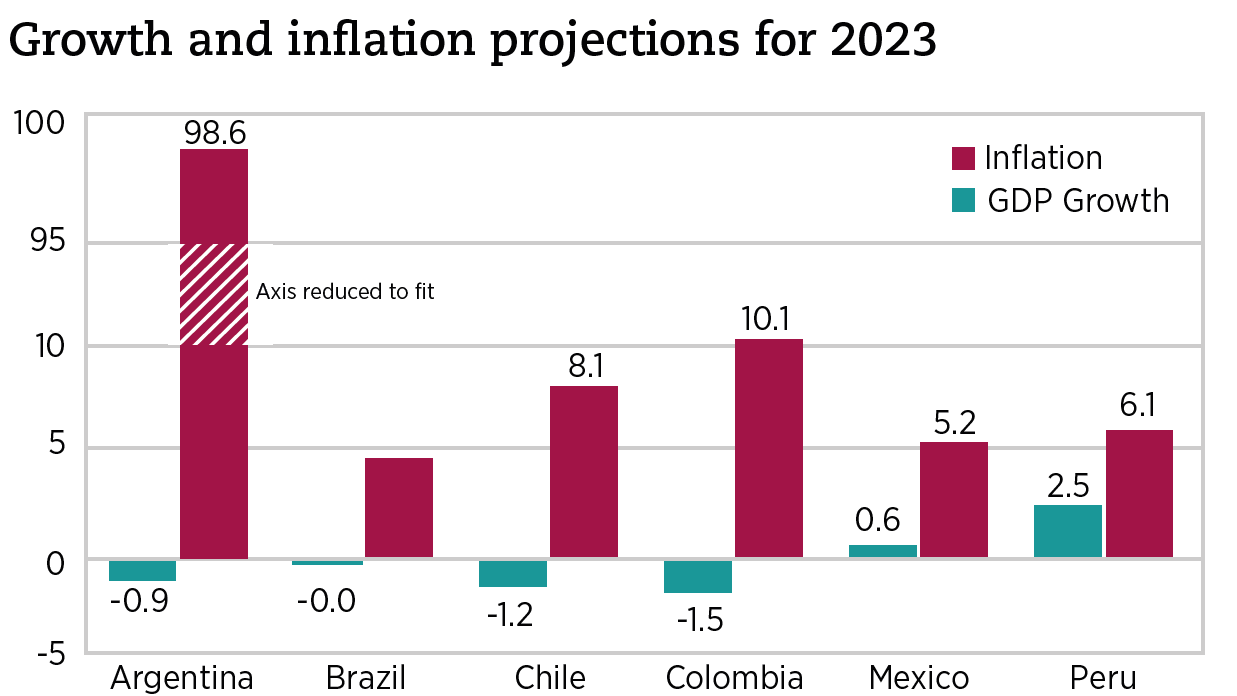

Governments throughout Latin America face dauting economic and political challenges in 2023. The region’s five largest economies are all expected to grow at less than 2% this year. Inflation has fallen from its peak in 2022 but remains high, raising the spectre of stagflation. Weak growth will have knock-on effects in labour markets, leading to job losses and growing informality. Further complicating matters, governments will be constrained by comparatively high debt burdens and borrowing costs. Failure to improve the fiscal situation will unleash financial volatility that will further depress investment and push up prices in the real economy.

The combination of high prices and weak labour markets is a recipe for social discontent and political instability. To stave off this threat, governments will have to make strategic use of limited fiscal resources by focusing spending on policies that support vulnerable households and create jobs. This means prioritising well-targeted cash transfers and subsidies and strategic public investment projects. Unfortunately, the region’s track record in this area is poor. Public resources are regularly squandered on pork barrel projects, bloated public sector payrolls, and inefficient subsidies—gasoline and pensions stand out—that mostly benefit the relatively well off. As a result, fiscal policy in Latin America does a poor job redistributing wealth and is an important reason why the region remains the world’s most unequal. Of course, removing subsidies and discretional spending has political costs. In Brazil and Colombia, for example, presidents Luiz Ignacio Lula de Silva (Lula) and Gustavo Petro face pressure to distribute public jobs and pork barrel projects to different parties to maintain fractious legislative coalitions.

Why is this a trilemma?

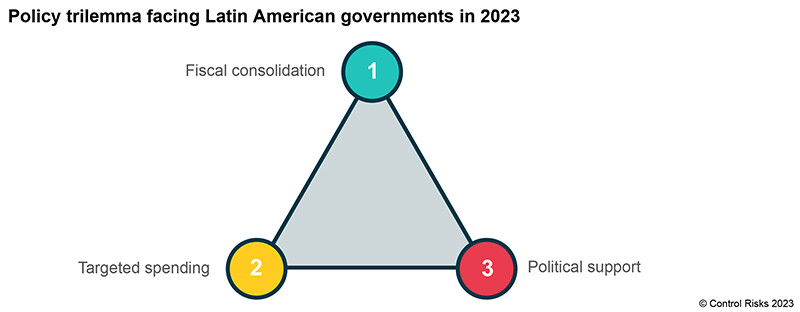

Governments thus face a policy trilemma in 2023. A trilemma occurs when three objectives cannot be obtained simultaneously (or only with great difficulty). In this case, governments will struggle to achieve fiscal consolidation (1) and targeted social spending (2) (which are necessary to deal with the challenging economic outlook) while also maintaining political support (3).

If governments want to increase spending to support the most vulnerable without compromising public finances - i.e. achieve 1 and 2 - they will need to cut pork and inefficient subsidies, risking political support (3). Governments can alternatively attempt to maintain this discretionary spending to solidify political alliances while also expanding targeted social programs (2 and 3), but this will likely come at the expense of fiscal consolidation (1). Finally, governments can opt for fiscal responsibility while maintaining politically useful but economically inefficient expenditures (1 and 3), but this will inevitably reduce the scope for new, targeted social measures (2).

Navigating the trilemma

Governments will struggle to square this triangle—resulting in policy uncertainty over the course of 2023.

The new Lula administration in Brazil demonstrates well the trade-offs involved in navigating the trilemma. His government has forged a large, diverse legislative coalition that will demand a steady stream of discretional spending. In its first weeks the administration, decided to maintain a fuel price subsidy - a classic inefficient but politically sensitive policy - while reaching an agreement to lift the spending cap to expand Bolsa Família cash transfers to low-income households and other social programmes. These moves set off worries that Lula would toss fiscal caution to the wind;

Finance Minister Fernando Haddad tried to calm those fears by announcing an already planned fiscal reform to increase revenue from companies and taxpayers with outstanding debts. The government discontinued the fuel subsidy in March and announced a new windfall tax on oil exports. Still, higher spending under Lula will likely lead to financial volatility and persistent concerns over fiscal stability, even if the risk of a default remains limited.

In Colombia, President Gustavo Petro has promised to uphold the fiscal rule even while pursuing an ambitious social agenda that foresees a greatly expanded role for the state in health care and pensions. To achieve this, the government has taken steps to make public spending more efficient. The Finance Ministry has begun to cut costly and regressive gasoline subsidies, even at the risk of a political backlash. Petro will also push for a major reform of Colombia’s pension system, which concentrates subsidies in the upper reaches of the income distribution. However, Congress last November rejected a proposal to tax high pensions, and Petro recently ruled out raising the pension age, underscoring the political challenges to more targeted social spending.

In the end, Petro will likely prioritise shoring up political support from his diverse coalition and increasing subsidies and transfers to low-income households. This means Colombia’s fiscal vulnerabilities will persist, although a major boost to the government’s balance sheet from record oil profits last year will postpone the reckoning until 2024.

Spiralling prices that pushed inflation to 11.6% last year were a major reason why Chile’s left-wing president Gabriel Boric saw his popularity plumet weeks after taking office in March 2022. The economy now faces a stagflationary scenario in 2023, with inflation expected to remain high at 8.1% while growth is likely to be negative. In response, Boric in early January announced a near doubling of cash transfers to support vulnerable households. While Chile’s solid fiscal indicators give him more room to manoeuvre, a major expansion of spending will make investors nervous, leading to more capital flight.

Among Latin America’s major economies, Mexico is an exception that proves the rule. Despite identifying with the left, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) has made an obsession of austerity. The government maintained a primary fiscal surplus even in 2020 when AMLO eschewed a major spending increase in response to the pandemic. Instead, he has slashed the budgets of numerous public programs, cut public jobs, and even axed entire agencies. Spending has focused on maintaining certain subsidies and investing in quixotic vanity projects such as the Tren Maya tourist train in southern Mexico and a huge refinery in AMLO’s home state of Tabasco. Counter-productive fiscal policy has contributed to anaemic growth, set to average 0.5% during AMLO’s six-year term (2018-2024).

Government austerity amid low growth would usually spell political disaster, forcing a change of course. AMLO’s political fortunes, however, seem to defy gravity. His approval rating remains above 60% after four-and-half years in office, and his Movement for National Regeneration (Morena) party continues to gain ground at the state and local level. In this way, AMLO’s teflon qualities have allowed him to escape the constraints facing other governments.

What it means for companies and investors

Talk of trilemmas may seem academic, but the trade-offs facing governments will affect the business environment in 2023. First, navigating multiple, often conflicting objectives (fiscal consolidation, targeted spending, political support) will drive policy volatility. This is already evident in the lack of policy clarity and frequent backtracking in key economies such as Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. This uncertainty will have knock on effects in financial markets, as investors will find ample reason to question government’s commitment to improving fiscal indicators. This will drive financial and currency volatility in 2023, especially amid lingering uncertainty over the pace of monetary policy normalisation in the United States and Europe.

In addition, while uncertainty will be the rule, there will be one key exception: new taxes on companies, as governments seek additional resources to mitigate the trade-offs of the trilemma. Finally, where institutions are especially weak - Ecuador and Peru come to mind - the challenging political and economic landscape will likely cause or prolong political instability and social unrest.

About the author: Theodore Kahn is an Associate Director in Control Risks’ market-leading political, operational and security risk analysis and forecasting team. He is an expert in Latin American politics and public policy, focusing on corruption, elections, fiscal policy and international trade and investments.