Next stop - Latin America

Canning House commissioned a paper to investigate the investment opportunities in the region’s massive transport infrastructure gap…

Canning House commissioned a paper to investigate the investment opportunities in the region’s massive transport infrastructure gap…

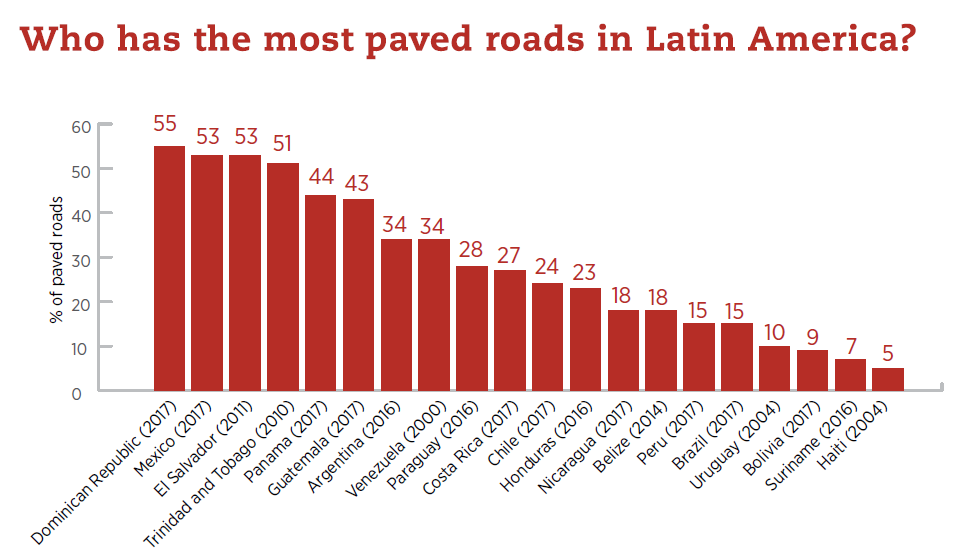

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) currently suffers a significant transport infrastructure gap compared to other world regions due to low levels of investment. Roads are predominantly used for transport in the region, but only 23% of roads are paved. The problem is different for railways, whose share of the transportation matrix is very limited, with LAC home to one of the “least extensive networks in the world,” according to the IDB.

LAC also has significant infrastructure gaps in urban mass transit, and its cities are among the world’s most congested. By way of comparison, Europe has 35 km/million. In many cities, authorities are trying to encourage people to leave their cars at home by improving public transportation, as well as walking and cycling infrastructure. One example is the recent wave of construction or expansion of metro systems.

Across the region, there have been noteworthy efforts to increase the number of electric buses operating as part of a drive to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, however they still represent just 4.67% of buses running in the cities monitored by the E-Bus Radar monitoring platform, reflecting the vast potential for further growth in the sector.

So Latin America needs to build more transport infrastructure but the challenge is to do it in a way that doesn’t harm communities or the environment. Governments and other stakeholders are increasingly trying to adopt a sustainable approach to infrastructure development in response to the concerns raised over social and environmental impacts of infrastructure projects. In general, awareness and implementation of Environment, Social, Governance (ESG) targets has been slower to develop in Latin America than in Europe, North America, or East Asia, but this is changing.

The other challenge is finance. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) have increased in popularity, with investment growing from $8bn in 2005 to $39bn in 2015, however PPPs still have to overcome their mixed reputation in the region. Further strengthening of ESG frameworks could encourage PPP deals, presenting a possible solution to the lack of public funding for infrastructure projects. LAC needs a huge amount of investment in overland transport infrastructure in order to close the infrastructure gap, which means that there are huge opportunities available for investors, developers, and other suppliers.

Road to nowhere

Transport in the region is predominantly road based, and 85% of freight is shipped by road. However, investment in road infrastructure has lagged behind the growth in transportation activities and only 23% of roads are paved, resulting in longer travel times and higher costs. There are large discrepancies between countries such as Mexico, where around 50% of roads are paved, and Peru, which is comparable in size but has paved less than 20% of its roads. As a region, only Sub-Saharan Africa has a lower percentage of paved roads (14.5%) than LAC, with other world regions averaging 60%-80%. Even the roads that are paved are often in a bad condition.

As for railways, their share of the transportation matrix is very limited, with LAC home to one of the “least extensive networks in the world,” according to the IDB. Passenger railways move only 38 million passengers per kilometre (pkm - the unit of measurement representing the transport of one passenger over one kilometre) per million people, compared to the global average of 484 million pkm per million people. In addition, the use of railways is concentrated in just a few countries, predominantly Brazil and Mexico. Railway networks have also suffered from a lack of coordination, with the use of multiple different gauges in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru affecting interoperability, according to a 2017 study. In Colombia, the use of narrow-gauge railways has saved money on construction costs but has limited performance, particularly in terms of lower operating speeds.

LAC also has significant infrastructure gaps in urban mass transit, with just 10km of mass transit per 1m habitants, which for the most part is still provided by small informal operators such as ‘combis’. By way of comparison, Europe has 35 km/million. The continued reliance on informal providers goes to show that formal systems are not responding to the needs of the population, which is evidenced by declining use of public transportation from the 1990s to 2010s, boosting the use of private vehicles. In comparison, Europe saw private transport use decrease for the period, with a slight increase in public transport use and a large increase in walking and cycling. In LAC, increased reliance on private vehicles coupled with inadequate road infrastructure has led to increased congestion and longer commuting times. Four LAC cities feature in a list of the world’s ten-most congested, and a number of cities – including Bogotá, Medellin, Mexico City, Quito, and Santiago – have imposed licence plate restriction policies with the aim of reducing traffic.

PPP solution?

Another solution to a paucity of public investment are PPPs. These contractual arrangements allow governments to fund infrastructure projects through concession agreements with private investors, such as toll roads. In LAC’s six largest economies, public investment in infrastructure fell from around 3.1% of GDP in the early 1980s to 0.8% of GDP from 1996-2001. This encouraged the use of PPPs, but poorly executed projects, such as highway concessions in Mexico that went bankrupt, led to a backlash in the late 1990s. More recently, PPPs have increased in popularity, with investment growing from $8bn in 2005 to $39bn in 2015, as many countries improved relevant regulations and set up dedicated government agencies.

Chile has seen particular success in using PPPs, most often for road infrastructure projects, while Colombia has strengthened its regulatory framework by passing a Public-Private Partnerships Act and an Infrastructure Act. Public investment as a share of total spending on infrastructure has been falling as private involvement increases, and several nations have used PPPs for projects such as electrifying public transport fleets.

However, the majority of infrastructure spending is still funded by the public sector, with only around 20% of spending funded by the private sector. LAC needs a huge amount of investment in overland transport infrastructure in order to close the infrastructure gap. This means there are plenty of opportunities out there, but PPPs have to overcome their mixed reputation in the region.

While studies show that they are less likely to suffer cost overruns or construction delays than public works, they are also frequently subject to contract renegotiation and can incur higher social costs and lower levels of service in nations that do not have adequately developed institutions. “The success of PPP projects requires countries to have legal and public governance systems that can provide transparency and effectiveness; policies, programmes, and projects need to be implemented in an integrated and coordinated manner across different government ministries and institutions; the willingness and capacity of the private sector to assume the corresponding risks need to be nurtured - all of this in a stable political environment with a strong consensus among political leaders and interest groups on the importance of people-first PPPs,” reads a report from the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (Eclac).

LAC suffers a significant transportation infrastructure gap due to a historic lack of investment, and it’s holding back development. There are myriad opportunities for industry due to the fact that national budgets continue to be constrained due to economic headwinds.