Frontier oil markets in the energy transition

Guyana and Suriname have a window of opportunity, write Theodore Kahn and Sebastián Fernández from Control Risks...

Guyana and Suriname have a window of opportunity, write Theodore Kahn and Sebastián Fernández from Control Risks...

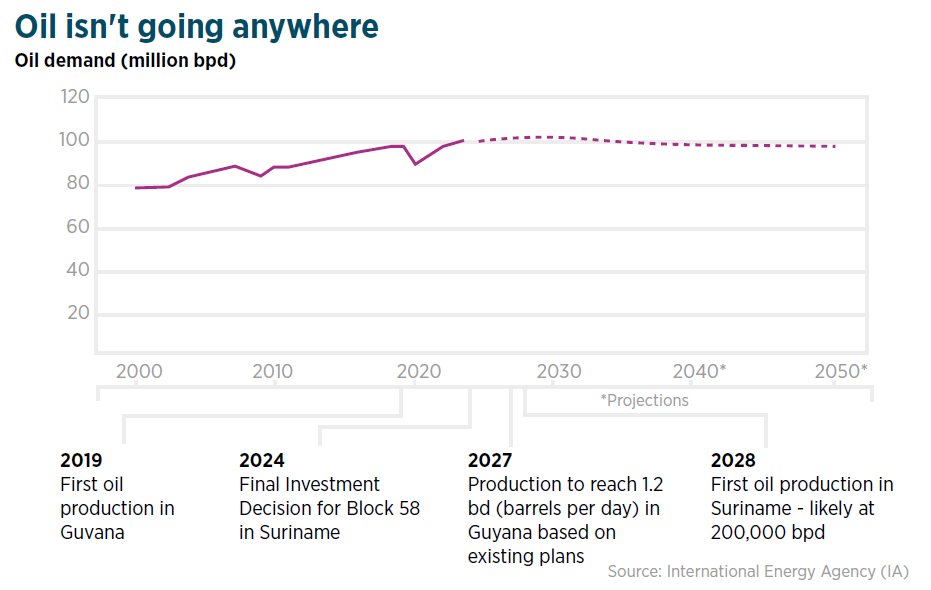

The fast rise of renewables and the urgent need to decarbonise have created a narrow window of opportunity for frontier oil markets. The International Energy Agency last month published new projections that show global demand for oil peaking before 2030 at around 100 million bpd (barrels per day). Investment in exploration remains below pre-pandemic levels despite a recent increase, and fewer companies and lenders are active in the segment. This has created major pressure on governments to attract investment, especially in frontier markets where risks are elevated.

Even if peak oil comes sooner than expected, however, global demand for oil and gas will remain high for decades. US supermajors like Exxon and Chevron have in the past month made enormous bets on hydrocarbons, underscoring their confidence in the industry’s future.

Against this backdrop, Guyana and Suriname are among the best-positioned frontier markets due to favourable policy frameworks, attractive geology and broadly favourable political environments. Guyana has already made the transition to established producer at breakneck pace. Since producing its first barrels in December 2019, output has increased rapidly to around 400,000 bpd.

While results of the country’s first-ever auction last month were disappointing – attracting bids from only six companies and groups for 14 offshore blocks – Guyana is poised to break the 1 million bpd barrier by 2027 based on companies’ existing production plans. In addition, acquisition last month by Chevron of Hess, one of Exxon’s partners in the Stabroek block, could lead to more aggressive drilling in the prolific fields.

While Suriname remains far behind its neighbour, there is still time to catch up. TotalEnergies, the operator of Block 58, the country’s first deepwater block, announced in September the launch of development studies for two main wells, which the company expects will produce 200,000 bpd by 2028. A Final Investment Decision (FID) on Block 58, expected in early 2024, will clarify oil production targets. Nevertheless, the potential is enormous: current projections show that Suriname’s two main fields likely hold 700 million barrels.

Dodging the resource curse

Guyana and Suriname face major challenges in dodging the resource curse and taking full advantage of their nascent oil wealth. In Guyana, the capacity of public institutions to manage a massive influx of investment is highly limited, creating bottlenecks for licensing and permits across industries. Key regulatory agencies lack technical know-how and independence, while decision-making authority is concentrated in top political leaders. As a result, regulatory enforcement from taxation to environmental compliance is weak, creating reputational risks for companies.

On the economic front, a shortage of workers – due to the small population and decades of brain drain – represents another challenge. Businesses in a range of industries have seen labour costs rise sharply over the last two years. A surge in construction has caused shortages of sand, stone, and other basic materials.

Finally, the country faces a major challenge around economic diversification. While the current government has actively courted investments in agriculture, health, ICT, and renewable energy, dependence on oil is almost inevitable given the economy´s diminutive size. This makes responsible management of oil revenues critical to the economy’s long-term fiscal stability.

Suriname, meanwhile, remains mired in an economic crisis that has led to three sovereign defaults since 2020. While IMF assistance has improved fiscal indicators somewhat over the past year, debt remains unsustainably high for a developing country (430% of public revenues in 2022). Negotiations with China (which holds approximately USD 400m of debt) remain stuck. Like Guyana, Suriname has limited institutional capacity to manage the influx of investments. Failure to use future oil revenue to improve living standards will create political instability and increase civil unrest risks after years of economic malaise.

Oil during decarbonisation

Guyana and Suriname have come under criticism for embracing oil despite the global imperative to slash carbon emissions. Governments in Georgetown and Paramaribo have stridently defended their plans to reap the benefits of oil wealth, while also looking to align with the decarbonisation imperative. Both governments have promoted nature-based solutions and carbon credits, taking advantage of their abundant natural capital. In 2022, Guyana reached a landmark deal with one of the Stabroek block companies to purchase $750 million of carbon credits, becoming the first country to issue them nationwide under jurisdictional REDD+ modality, which tracks emissions reductions at the national level (as opposed to specific projects).

demand for oil and gas will remain high for decades. US supermajors like Exxon and Chevron have in the past month made enormous bets on hydrocarbons, underscoring their confidence in the industry’s future.

Simultaneously, Suriname is seeking to become the first nation to sell carbon offsets under the framework established by the 2015 Paris Agreement, known as Internationally Transferable Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs). The Surinamese government has committed to using the funds to combat deforestation, a key concern in the country given its 93% rainforest coverage.

Still, governments and companies participating in these initiatives will be exposed to accusations of greenwashing. Guyana’s carbon credit scheme, for example, has been questioned for its lack of additionality (on the basis that its vast forests are not at risk of deforestation). The government has also been criticised for pushing a major gas-fuelled power plant project rather than prioritising renewable generation.