2022 Weather Forecast: Plenty of Sun and Wind in Latin America

New renewable technologies are needed to help the region replace failing hydro and meet ambitious climate change targets…

Latin America has more fresh water per person than any other place on earth. Although it probably doesn’t feel like that to most Brazilians right now. A historic drought has left the country’s hydroelectric dams starved of water, limiting its main source of electricity generation. President Jair Bolsonaro will be hoping that the rainy season arrives before he has to enforce power rationing on homes and businesses, which would be a political nightmare in the run-up to next year’s elections.

But even if the rains do save Bolsonaro, the episode is a stark warning to Latin American governments. For decades the region has been an energy transition pioneer, building the greenest electricity grids in the world based mainly on hydroelectric plants. But now climate change looks set to undermine that progress. Rainfall in the region is decreasing and becoming more erratic, which makes hydroelectric plants a less dependable source of power. What’s more, this is happening exactly when Latin American governments are signing up to ambitious net-zero emissions pledges. The only solution is to develop more wind and solar power.

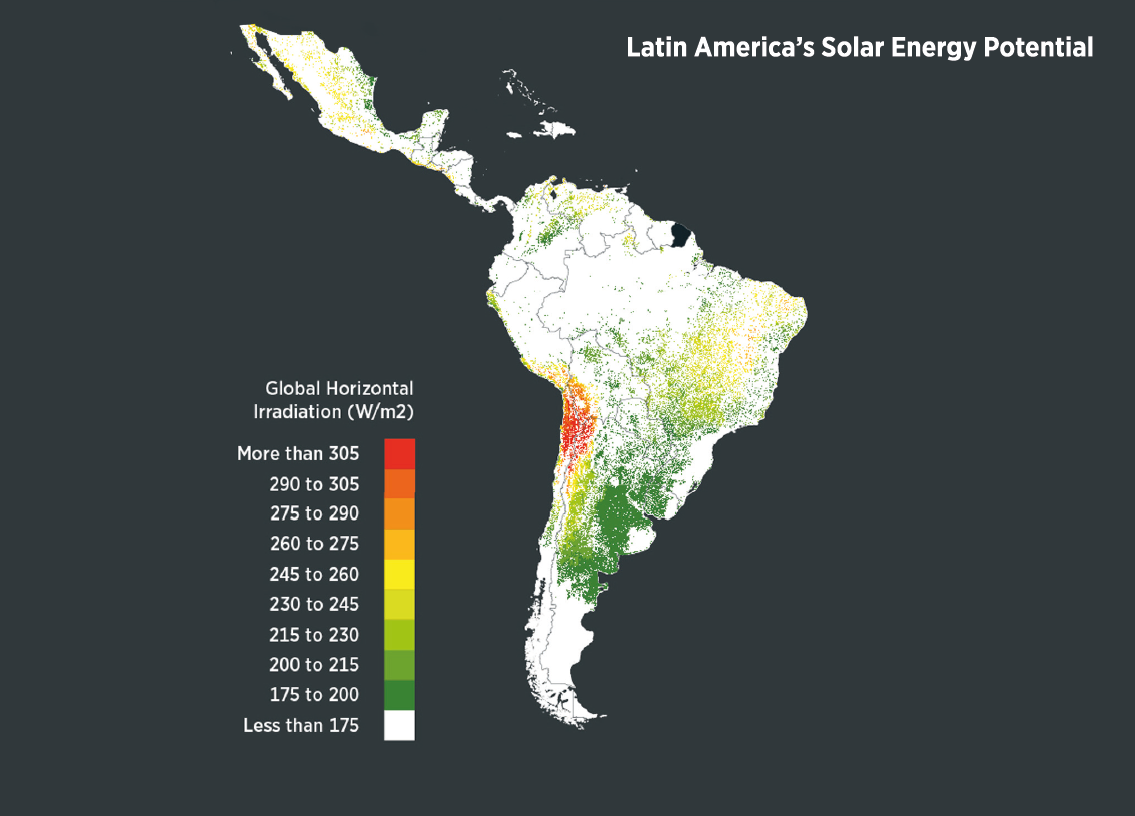

The good news is that Latin America has incredible solar and wind potential. For example, Chile’s Atacama Desert has some of the highest solar irradiance levels in the world and panels there can operate at 37% efficiency factor. Moreover, Chile has capitalised on its natural advantages, with a series of renewable energy auctions that persuaded power developers to build solar farms in the country. Over the last decade the country has added 1,000MW per year of solar energy and non-hydro renewable power generation now accounts for 25% of the country’s electricity.

Colombia is another brightspot. For years the country’s heavy hydro dependency meant it didn’t develop solar or wind. In 2019 the country had just one solar plant and one wind farm, with a combined installed capacity of only 30 MW. Yet a series of successful renewable energy auctions has unleashed a wave of solar and wind projects that, by next year, should account for 12% of the country’s grid.

Solar and Wind

Those success stories are positive but if Latin America is to meet its climate change commitments while also replacing falling hydropower production then it will need much more wind and solar. Martin Vogt, CEO of MPC Energy Solutions, a Latin America-focused independent power producer, believes that state-run energy auctions aren’t enough.

“We are very sceptical about the results of auctions. You see the results but then those projects aren’t always built because developers win the bids and try to flip the PPAs and sell them back to the market. Governments in Latin America are slowly realising that this isn’t helping them meet their goals of building installed renewable capacity.”

Instead, Vogt believes that industrial and commercial electricity consumers will drive the energy transition in Latin America. “We want to focus on corporate users because we believe that is the future of renewable energy. The last decade of the energy transition was dominated by governments, who set feed-in tariffs for utility-scale projects. Then it became a type of hybrid, with the governments defining auction frameworks, while the private sector competed to set the final prices. In that second phase the state’s role evolved to become simply the connection between the renewable energy producer and the off-taker. But we are seeing from different region like US, Iberia or Scandinavia that the next stage is corporate demand. The government is no longer setting the regulatory framework but the private sector demands renewable energy from IPPs. These tend to be smaller projects than the utility-scale renewable plants that have dominated until now.”

Vogt’s vision ties in neatly with COP26, which is looking for the private-sector to contribute more in the fight against climate change. Indeed, with state finances across Latin America stretched by the pandemic, corporate clients are a more feasible source of finance for renewable energy projects.

“In a typical situation, a multinational will have a renewable energy policy that has been set in the boardroom in North America or Europe”, says Vogt. “Yet they are operating in emerging markets with unreliable and expensive grids. Until now they have relied on diesel generator sets to provide back-up power during blackouts as they have to produce 24/7, which is sub-optimal from a price perspective and also in terms of their carbon footprint. We offer them a solution that combines solar power with battery storage and LNG gas support, to give them complete independence from the grid, lower energy costs and a greener energy profile.”

Tiago Alves, the co-founder of Solar Americas, a UK-based, Latin America-focused renewable energy developer, agrees that business innovation is key. “Latin America has a big role in fighting climate change. And, from an investment point of view, the biggest upside to the renewable transition story can be found in Latin America. International investors don’t realise how much growth and margin there is in Latin American energy markets. The market traditionally is very biased to existing notions of PPAs etc and we want to develop new business models. We want to spread the risk-reward balance between clients and developers. Clearly developing a solar farm in Latin America is not that revolutionary in terms of technology but the difference we bring is on the business model. By working with energy offtakers we can rework the economics of renewable energy projects in Brazil.

“The idea is that we are providing solutions for industrial offtakers. The usual approach for developers is to sell energy directly to offtakers but we have a different concept. We want involve them in the project, offering them equity. That means we benefit from their pool of capital, while they gain from the investment returns, so it’s a real win-win.

“And because renewable self-generation is such a good investment in Brazil, these medium-sized companies don’t just want to be a simple offtaker and leave money on the table. They would like to develop a project and share the rewards. Two-thirds of the cost of a solar farm is the capital and our advantage is that we can bring expertise and cheap funding from the UK to develop these projects while also giving the offtakers the option of participating in the investment.”

Colombia, Mexico and Panama

MPC Energy Solutions has spent the last few years analysing renewable energy investment opportunities throughout Latin America. We asked Vogt to share his favourite markets in the region. “In Colombia we identified an opportunity back in 2017, when we began to develop projects from scratch with Martifer Renewables. Colombia was the last big white spot in the map where no renewable energy had been built. It has 50 million people, is Latin America’s fourth-largest economy yet it is mainly powered by hydro and coal. It is an OECD, investment-grade economy with strong local utility companies and a government that is pro investment. In 2017, it had basically zero renewable installed capacity but has ambitious targets for the next decade. When the new government came to power it showed it was serious about wanting to diversify. They realise hydro is vulnerable to climate change and coal a source of such climate change. Increased drought causes falling hydro production, meaning that LNG and renewables are the way to go.

“We also like Mexico a lot. The energy reform in 2014, especially the changes to CFE, created a huge boom in Mexican renewables. The capital demands of US investors pushed up valuations to unattractive levels. But now prices have gone down with fears about Amlo and his new Energy Industry Law, which will make life more difficult for private renewable energy generators. However, at MPC Energy Solutions we take a long-term view and realise that the current political volatility is creating a buyer’s market. Projects that were trading on 8% IRR are now available at 14%, so it makes a lot of sense for us right now. Some investors are being forced to sell their Mexican assets because their mandates mean that they can’t sit out a political crisis. But when we look at 25-year power demand in Mexico we see that this is just a blip.

“Panama is interesting because it is a fantastic country to invest in. There is a strong private business culture and energy sector with few very strong local renewable players, which makes it attractive to us. We are less keen on Chile, which is the most mature energy market in the region and there is a premium compared to the rest of Latin America. Brazil is so big, with lots of local capital and vertically-integrated players that it is hard for us to get a foot in the door. The local currency issue also makes it difficult for international investors.”

Brazil

Solar Americas Capital was launched this year by two Brazilians in London, who plan to use British capital to build 2 GW of solar power in Brazil by 2026. Alves explains, why he sees an opportunity in the country. “Brazil has a good net metering system and a steadily improving regulatory environment. Brazil often gets a bad press when it comes to renewables, especially with Bolsonaro. You get the dramatic headlines – ‘Bolsonaro to tax the sun’. But the reality on the ground isn’t that bad. Our target market is industrial users that want to generate their own renewable power – known as self-generation in Brazil – a model that receives lots regulatory advantages and incentives.

“One interesting element of the Brazilian market is mid-tier corporates. The small guys – residential users and shops – are too small for us to work with. While Brazil’s biggest corporations can easily develop their own renewable energy solutions. Yet there is a huge swathe of medium-sized companies, with annual revenues of several hundred million dollars, that need a partner to build a solar park.

“I guess the most surprising news for your readers is that Brazil has a pro-business environment that allows you to choose what you want to build and how you build it. You only have to pay for transmission costs from project to user. You are free to sell excess power on the spot market for a fair price but there is also the option to ‘lend and borrow’ power from the grid. Because Brazil has so much hydro power, the grid likes to use distributed solar as a battery system. That is to say, during the day, when there is lots of sunshine, the grid receives the excess solar power. That allows is to reduce hydro use, which can be saved for the evening peak. That means if a self generator produces 100 Mwh during a day, the offtaker can consume 50 Mwh, ‘lend’ 50Mwh to the grid and then get that power back when it needs it. The advantage with this power sharing agreement is that you aren’t at the mercy of volatile prices in the sport markets.”

Governments across the region have lots of incentives to add solar and wind power to their national grids. Renewable energy is popular with voters, it helps reduce imports of fossil fuels and it stabilises grids that are being weakened by changing rainfall patterns. But the states can’t do it all themselves. Latin America needs massive inflows of international capital to build renewable energy projects.