Bet on Brazil

Brazil will benefit from the two major themes driving the world economy over the next two decades – the energy transition and global population growth...

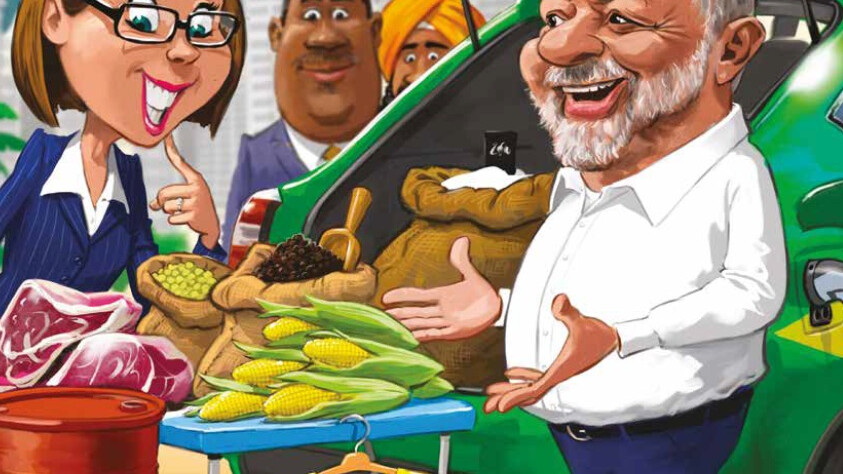

Brazilians across the political spectrum reacted passionately to socialist Lula’s election victory. The supporters of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva took to the streets across Latin America’s largest economy to celebrate with red flags and convoys of honking cars. Meanwhile those of his defeated rival, outgoing president Jair Bolsonaro held mass prayer meetings for their country’s impending challenges.

The passion was understandable, given the bitter election had been billed as a historical crossroads for the country. The market reaction was more muted, with early losses on Monday morning, recouped by lunch. Perhaps that shows the two rivals are far more similar – in economic terms at least - than their supporters would like to admit. After all, in their respective terms as president, both spent too much, meddled in the national oil company, Petrobras, and faced plenty of corruption claims.

Brazil grows despite – not because – of its politicians and regardless of who won, the country should reward investors. Brazil will benefit from the two major themes driving the world economy over the next two decades – the energy transition and global population growth.

Don’t fear Lula

In theory, Lula presents some worries for investors. One major difference between the two candidates is that Bolsonaro privatised state companies, while Lula wants them to play a bigger role in the economy. Lula is also keen to do away with the fiscal restriction that caps budget growth to the level of inflation in the country. Yet Lula’s history proves him a more moderate president than campaigner. And even if he wanted to be radical, Brazil’s political system of proportional representation limits his power. No party ever wins a majority in Congress, the federal legislative body, which means the president has to cut deals with the ‘Centrao’ (big centre) block of lawmakers. It is pork barrel politics, where presidents exchange local funding for supportive votes and, sadly, it probably prevents some of the reforms Brazil needs. But, on the plus side, it prevents presidents from implementing an extremist platform.

Another check on Lula is that while he won the presidency, centre-right politicians secured their power of the senate and the congress in the same election. Bolsonaro’s party also controls three of Brazil’s most populous states, which is significant in the country’s federal system, where most of the regulations that impact businesses are set at a local level. The most valid criticism of Lula is his corruption, as his administration was involved in the largest graft scandal in Brazil’s history. However, the consequence of that is improved protocols and increased scrutiny – it is hard to imagine his government attempting the same this time around.

Lula’s handpicked successor oversaw the worst recession in Brazilian history but his own two terms – from 2003 to 2011 – coincided with an economic boom. Judging by historical Brazilian standards you would have to say that Lula – much like Bolsonaro – was a relatively competent, pro-growth president.

EM darling

The most significant aspect of the Brazilian election, isn’t who won but how efficiently the system worked. An incredibly tight vote – 50.9% to Lula and 49.1% to Bolsonaro – was decided within hours and while key allies of Bolsonaro quickly congratulated Lula. Brazil is one of the most efficient large democracies in the world and a marked contrast to fellow Brics, Russia and China. The democratic dividend is often ignored by investors when autocracies are going well, but the erratic decisions of Russian leader, Vladimir Putin, and – to a lesser extent, China’s Xi Jiping, show why investors should value democracies.

Indeed, Brazil has shone this year, amidst an historic sell-off of emerging markets. As Julian Rimmer puts it so well in the Financial Times: “At a moment when most of EM is radioactive, Brazil offers something the others can’t: democracy and growth.” Brazil’s GDP growth is set to come in at 2.6% in 2022, above analyst expectations at the start of the year and only just behind China’s expected 3% growth.

One reason is that Brazil has benefited indirectly from the Ukraine war. Soaring commodity prices for food, fuel and raw materials have fuelled Brazilian exports. As a result, the Brazilian real is one of the few currencies that has managed to gain against the all-powerful dollar and is up 7% so far this yar. But while the commodity crunch caused by the war is hopefully a short-lived phenomenon, Brazil’s world-leading agribusiness, mining and energy industries will continue to thrive. They will be driven by the two most powerful shaping the world economy – the energy transition and the growing global population.

Heat and eat

Most economic analysis of Brazil is gloomy. Growth might be good in 2022, concede analysts, such as Capital Economics, but in the coming years it will hover between 1.5% and 2%. Perhaps, but steady growth of almost 2% is better than the recessions awaiting most of the developed world. Brazil is also doing well with inflation, a traditional bugbear for the Brazilian economy, which declined from a peak of 12% in April and is now at 8%. For the first time in my lifetime Brazil will have lower annual inflation than the UK. The success is down to the central bank – made independent by Bolsonaro – which began to increase rates in March 2021, while the hapless Bank of England was still insisting that inflation was transitory.

Unfortunately, Brazil’s politicians aren’t as thrifty as their central bankers. Bolsonaro pumped the economy with pre-election spending that ratings agency Fitch believes could swell the fiscal deficit to 7.5% by the end of the year. And Lula, a famous proponent of state spending, is hardly likely to be more austere. But I’m not asking you to invest in Brazilian government bonds. What excites me is the country’s booming export sector. Put simply, Brazil makes what the world needs. And as our world is upended by the energy transition and rapid population growth, demand for Brazil’s goods will soar.

The world can’t fight climate change without Brazil. And as pressure grows to slow global warming, more money will flow into the country. Its main asset is the Amazon rainforest, which is home to more biodiversity than anywhere else on the planet. A healthy Amazon rainforest would act as the planet’s lungs, absorbing huge quantities of C02 and releasing fresh oxygen. Under Bolsonaro, deforestation increased, which led some scientists to worry that fires in the rainforest were releasing more C02 than it could capture. Lula has a proven track record of combatting deforestation when he was last president and international donor countries, like Norway, have already announced plans to resume funding Amazon projects. Lula’s stance on the environment is great for the planet but it will also yield economic benefits. Deforestation was a major sticking point in ratifying a trade deal between the EU and Mercosur – South American trade bloc of which Brazil is the largest member. As William Jackson of Capital Economics notes, “were Lula to get the trade deal over the line, it would be a move towards trade liberalisation, which is one -among many – factors holding back productivity growth in the country.”

Brazil’s next globally significant climate change asset is its mining industry. That might seem to contradict the previous paragraph but Brazil’s iron ore and nickel are essential for the energy transition. Brazil has the world’s fourth-largest reserves of nickel – a metal that is used in electric vehicle batteries. At present the main use of nickel is stainless steel, as adding it to the mix helps make steel more resistant to extreme temperatures and corrosion, while batteries account for just 6% of overall nickel demand. But S&P Global expects that to reach 35% by 2030 as electric vehicle production jumps.

Brazil also has the world’s second-largest iron ore reserves. Iron ore isn’t a ‘clean tech’ metal, directly associated with renewable energy. But a little-understood aspect of the ambitious plan to electrify the global economy is that it will turn the world into one big construction project. Switching from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles needs the build-out of a network of charging stations. And if these electric vehicles are going to reduce emissions then they must be powered by renewable energy, which means adding huge amounts of wind and solar plants, which all then have to be hooked up to the grid. The energy transition involves overhauling the entire planet’s built environment. It’s no coincidence that Brazil’s golden decade at the start of this century coincided with China’s building boom. The South American iron ore producer will benefit from the electrification building boom too.

Feed the world

Brazil is well established as an agricultural superpower and, according to credible studies from its state-run agricultural research agency, the country’s food production feeds 10% of the world’s population. It is the world’s largest exporter of beef, soybean, sugar and coffee. It is also very near the top in corn, cotton and pork. Depending on how it is measured, agribusiness now accounts for 25% of the Brazilian economy. The sector’s massive growth has been partly responsible for the increase in deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. Yet Lula has been careful not to declare direct war on the influential agribusiness lobby. Instead, he has been looking for innovative solutions, such as offering subsidised loans to encourage farmers to plant non rainforest land. Without doubt, companies with questionable practices will come under pressure from the new administration as it restores much-needed funding to environmental agencies. But serious players will be able to benefit from growing food demand.

The US Census Bureau estimates the world population will hit 8 billion in mid-November 2022. That will grow to almost 10 billion by 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100. Over the same period, an increase in extreme weather events – that most scientists attribute to manmade climate change – will undermine farming production. Of course, Brazil isn’t the world’s only breadbasket but recent conflicts have shown that it is one of the most reliable. Food exports have been used as a weapon in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and it is likely that something similar could happen if China were ever to attempt to invade Taiwan. Brazil, which happily sells both to the US and China, will see demand increase as the global population rises.

The same dynamics described for food apply to energy. Brazil is the largest oil producer in Latin America, and its production has climbed to 3 million barrels per day, from 2 million barrels of oil per day in 2012. Consultants McKinsey believe it could reach almost 4 million barrels per day by 2035. The massive growth is down to the giant ‘pre-salt’ offshore fields that were discovered in Lula’s first spell as president but, because of the technical difficulties of extraction, are only staring to be properly exploited.

This oil wealth might seem to contradict Brazil’s climate change appeal but hydrocarbons are an important part of the transition. In his recent book, The New Map, energy analyst, Daniel Yergin, posits a ‘planning scenario’ in which the current consumption of 100 million barrels of oil per day, rises to 113 million barrels by 2050. One reason is that cars and light duty vehicles only account for 33% of oil demand, so even if we manage to replace the entire global fleet to EVs we will still need more oil for petrochemicals, aviation fuel, asphalt etc for a rising population.

Linked to both energy and food is Brazil’s biofuel production. Brazil is the world’s second-largest producer and consumer of biofuels. That was led by the sugar industry in the 1970s but now modern biofuels can use a much wider range of feedstock, such as plant waste, dead animals and used vegetable oil. As the technology improves Brazil will be able to extract ever more value from its agricultural waste products. You wouldn’t think it from the press coverage surrounding the election but Brazil has been the standout emerging market in 2022. Despite that success its stockmarket still looks attractive, with the Bovespa trading on a price-to-earnings ratio of just seven compared to the MSCI Emerging Markets average of ten. Commodities – and Brazilian politicians – are inherently volatile and investors can’t predict what will happen in two years’ time. But if you can afford to take a longer time horizon you can profit as Brazil’s exporters feed, heat and move the world.

A version of this article was first published in MoneyWeek on the 4th of November 2022